AI Art Is Directing

A response to the New Yorker article “Why A.I. Isn’t Going to Make Art” by Ted Chiang.

Most writing about AI is tiresome because it is written by people who aren’t practitioners. It’s like reading about the future of travel from people who have never driven a car. The recent New Yorker article “Why A.I. Isn’t Going to Make Art” by Ted Chiang is no different and shows how most media is thinking about AI in ways that anyone with a passing experience using these tools can recognize as inaccurate.

AI Art Involves Making Creative Choices

The most significant false claim that Ted Chiang makes is that AI art does not involve making creative choices:

Is there a similar opportunity to make a vast number of choices using a text-to-image generator? I think the answer is no. An artist—whether working digitally or with paint—implicitly makes far more decisions during the process of making a painting than would fit into a text prompt of a few hundred words.

This is funny because he immediately contradicts himself in the next paragraph:

We can imagine a text-to-image generator that, over the course of many sessions, lets you enter tens of thousands of words into its text box to enable extremely fine-grained control over the image you’re producing; this would be something analogous to Photoshop with a purely textual interface. I’d say that a person could use such a program and still deserve to be called an artist. The film director Bennett Miller has used DALL-E 2 to generate some very striking images that have been exhibited at the Gagosian gallery; to create them, he crafted detailed text prompts and then instructed DALL-E to revise and manipulate the generated images again and again. He generated more than a hundred thousand images to arrive at the twenty images in the exhibit.

This has been my process as well. For the art book The Gods of AI, I generated over 20,000 images. For the music album Villains, I generated over 100 versions of the same song in some instances before finding the one I released. Every other AI creator I know uses a similar process. Even Chiang recognizes these as creative choices.

Even when someone uses the first output of an AI, it is a creative choice to use that output. Rather than denying human creative choices, AI shifts creative choices to those of a director.

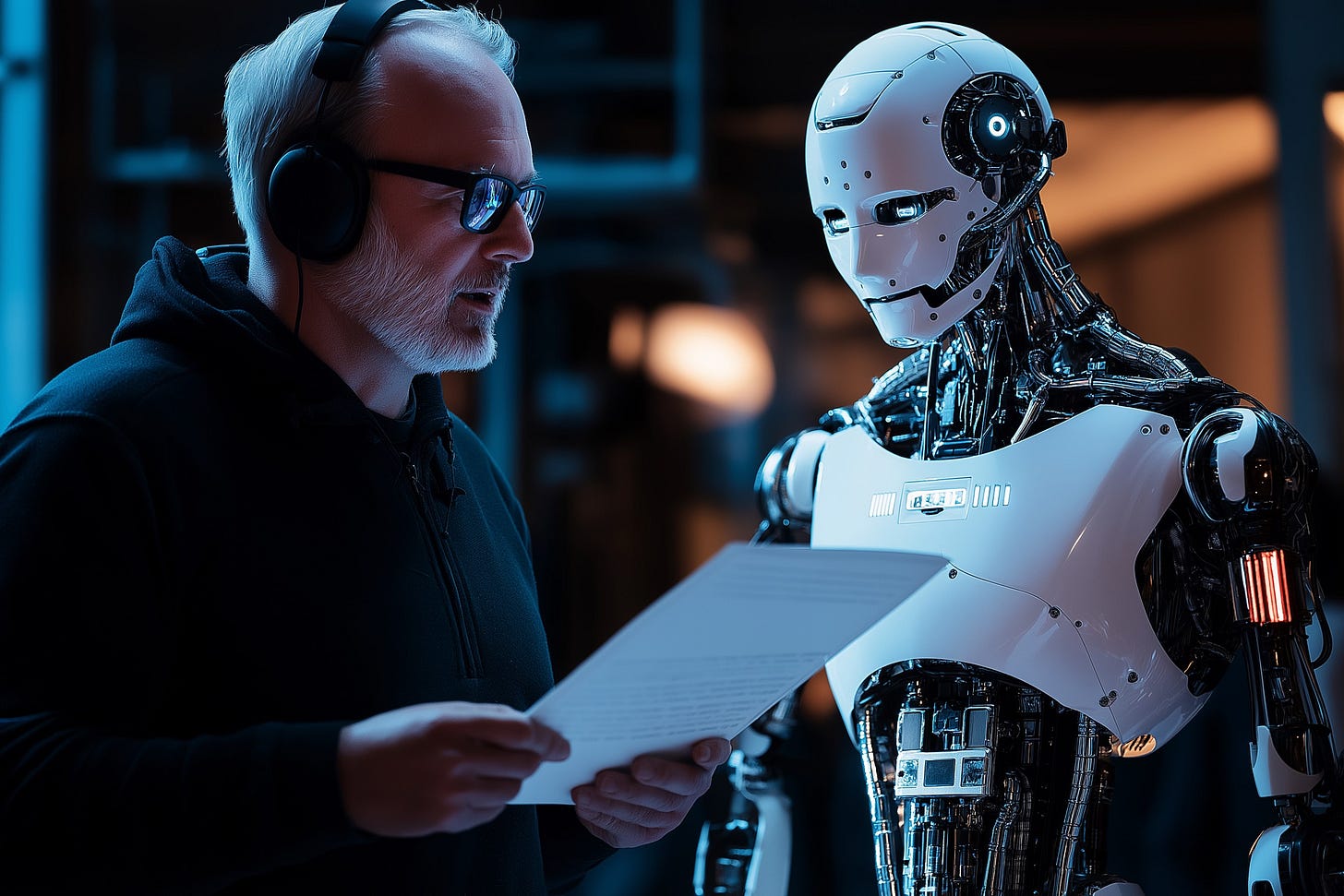

Prompting is directing. Usually, directors do not act in their own films, hold the camera, build their own sets, etc. They “prompt” their cast and crew to create their vision. AI is simply another collaborator.

Even though the director is not doing every job on their set, they are typically recognized as the “author” of the film. Even though AI artists do not draw their own pictures, like film directors, they direct the AI to produce their vision.

When writers protest that AI artists, I think they are devaluing the artistic skill of directing because they want the value of their work seen. Cast and crew make valuable creative choices. However, those choices flow from the direction. Directing is an artistic skill that involves numerous creative choices, even if those choices are executed by other artists — be they human or AI.

AI Art Still Requires Work And Has Value

Chiang makes two false assumptions here:

The companies promoting generative-A.I. programs claim that they will unleash creativity. In essence, they are saying that art can be all inspiration and no perspiration—but these things cannot be easily separated.

First, they are separate. This is the labor theory of value applied to art — the idea that the more effort put into a piece the better it must be. It’s false. Terrible films are made from millions of dollars and hundreds of hours of work. Brilliant art can be made from a flash of insight or a moment of action. The amount of effort put into a work of art does not determine its value.

Belief in the labor theory of art causes artists to believe they have to suffer to create great art or that their art deserves recognition because they worked so hard on it. It also causes artists to miss valuable artistic opportunities because they seem “easy” and artists associate ease with lack of value.

While there are times that “perspiration” can lead to great art — and I say this as someone who spent six years on a single documentary (without AI) and is currently in the midst of the slow process of rewriting a novel (without AI) — the value of the final product can be evaluated separately from the process that created it.

This romanticization of struggle is behind the resistance many artists have to AI tools. If value is tied to struggle, then tools that make art easier to make also reduce the value of that art. Taken to its logical conclusion, this philosophy should lead to artists tossing out their computers and going back to stone and chisel.

However, this resistance includes a second false assumption: that AI art does not involve creative work. Saying that AI art doesn’t involve “perspiration” because the AI does work for you is like saying that directing doesn’t involve work because your cast and crew do it for you. AI removes technical and physical challenges, but creative ones remain. Like a cast and crew, AI requires clear direction or it will make creative choices contrary to your vision. Since AI can create anything, it forces you to clarify your vision. The work remains.

Bad AI Art Is Due To Robotic Humans

Because AI art critics don’t recognize the skill of directing, they often create a false dichotomy between 100% AI-generated art and human art, when most AI art is AI-created and human-directed.

Chiang does this throughout the article when he suggests that human-created art is special because it has an “intention to communicate” that AI lacks. Yet if I prompt AI to write “I’m happy to see you” then there is a human “intention to communicate something” behind what it generates. AI is a tool. Where AI feels robotic, it is due to human error.

Human communication is more robotic than Chiang acknowledges. When someone writes “I hope this email finds you well” they do not care how this email finds you. When a cashier says “have a nice day,” they do not care about your day. When a new acquaintance says “how are you?” they do not want to hear your full mental and emotional state. They are running a social script.

If you direct AI to run a social script for you, it will feel robotic, because you are being robotic. The reason most business writing can be outsourced to AI is that it already lacks human creativity, which Chiang acknowledges:

Not all writing needs to be creative, or heartfelt, or even particularly good; sometimes it simply needs to exist. Such writing might support other goals, such as attracting views for advertising or satisfying bureaucratic requirements. When people are required to produce such text, we can hardly blame them for using whatever tools are available to accelerate the process. But is the world better off with more documents that have had minimal effort expended on them?

It would, but the problem here isn’t AI; it’s humans. Humans are the real robots.

We are entering an era where someone might use a large language model to generate a document out of a bulleted list, and send it to a person who will use a large language model to condense that document into a bulleted list. Can anyone seriously argue that this is an improvement?

No. It’s acceleration. AI empowers people, but there is no moral dictate on that power. If everyone has a full AI crew and I direct mine to make movies and others direct theirs to make power points, is that a reflection of AI or us?

The complaints people have about AI are complaints about humans, specifically what humans with bad direction will do with increased power. The solution isn’t to nerf AI but to change human consciousness, which you could do — with AI art.

If You Want To Understand AI, Use It

Chaing bemoans that “Generative A.I. appeals to people who think they can express themselves in a medium without actually working in that medium.” If he wants to understand AI art, perhaps he should take his own advice and work in the medium before opining about it in the pages of the New Yorker.

The idea that AI art involves directing is immediately obvious to anyone who has used these tools. Every AI tool has a box where you write your prompt - i.e. your direction. Complaining that an AI artist doesn’t work in the medium they’re creating with AI is like complaining that a director can’t act. We know. That’s not the skill they’re using and making that complaint shows a shocking level of ignorance about the arform.

Instead of defending human art, articles like this erase the human artists behind AI. Every piece of AI art was prompted by someone and shared with intention. AI could not have made it without them. You can make AI art too if you learn to direct.

Excellent, educational, and thought-proving essay, Brendon. You've helped me understand A.I. as a tool for creative expression and communication. Like any tool, A.I. can be used for creative or destructive purposes, for good or for bad. You've also made me curious to try A.I. and see what I can make with it.